Project Description

Copyright: DFRLab, Atlantic Council, August 19, 2019.

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict has long been a global battle, fought by hundreds of proxies in dozens of national capitals by way of political, economic, and cultural pressure. As the internet has evolved, so have the tools used to wage this information struggle.

The latest innovation — a pro-Israel smartphone app that seeds and amplifies pro-Israel messages across social media — saw its first major test in May 2019. It offered a glimpse of the novel methods by which future influence campaigns will be conducted and information wars won.

At approximately 12:00 a.m. EDT on May 4, Hamas militants operating out of Gaza fired the first of more than 600 unguided rockets into Israeli territory. Their indiscriminate bombardment continued until a negotiated ceasefire took effect at 9:30 p.m. on May 5. Four Israeli civilians were killed over the two-day period.

The Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) fought back with airstrikes and a fuel blockade as it mobilized for a possible invasion of Gaza. Notably, the IDF also resumed its practice of the targeted assassination of individual Hamas members, abandoned since 2014. An estimated 22 Palestinians were killed, roughly half of them civilians.

As with previous conflicts, the fight between Hamas and the IDF was mirrored by a global information war. Hamas sought to entangle itself with more general pro-Palestinian sentiment, relying on a loosely organized network of supporters. By contrast, Israel used a more centralized model, built around amplification of the communications of both the IDF and Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Israel also turned to friendly civil society groups among the Jewish diaspora.

One such online proxy was Act.IL, which describes itself as an “Online Community for Israel.” Act.IL administers a smartphone app that assigns users a series of “missions” — typically a comment, retweet, or “like” — intended to boost pro-Israel content across multiple platforms. Through these missions, Act.IL claims to have reached millions of people. Although there has been significant media coverage of Act.IL (critics describe it as “digital political astroturfing”), no independent empirical examination of its impact has yet been conducted.

The DFRLab monitored Act.IL missions during May 4–5 and captured corresponding Facebook, Twitter, and web activity. The results of this investigation illustrate the manner in which Act.IL orchestrates coordinated, centrally planned influence operations in order to promote Israeli public diplomacy goals online.

This analysis, however, also reveals that the Act.IL app’s effectiveness has been overstated by champions and critics alike. Out of a userbase of 17,500, the app elicited approximately 300 publicly trackable pageviews and 243 Facebook interactions for its emergency landing page. It elicited an average of only 12 retweets each for the Twitter messages it sought to amplify.

Indeed, the principal impact of the Act.IL app has been to cast doubt on the authenticity of numerous other expressions of Israeli support, in contravention of Israeli public diplomacy goals.

A Closer Look at Act.IL

The Act.IL smartphone app launched in June 2017 as part of 4IL, a web campaign intended to bolster Israeli public diplomacy (also called hasbara,Hebrew for “explaining”). The initiative was unveiled at New York’s Celebrate Israel Parade and Festival by Gilad Erdan, a powerful Likud party member who serves as Israel’s Minister of Public Security, Minister of Strategic Affairs, and Minister of Information. (Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu is the head of the Likud party.)

Erdan described 4IL as the “Iron Dome of Truth.” He said that “cell phones are the number one weapon against [Israel]” and that 4IL represented an “international effort to unite Israel’s supporters around the globe and provide them… with resources to spread the truth.” 4IL’s launch was accompanied by a trailer featuring Israeli actress Ariel Mortman and model Titi Aynaw, who directed viewers to download the Act.IL app.

Although the broader 4IL initiative is sponsored by the Israeli Ministry of Strategic Affairs and Public Diplomacy, Act.IL is ostensibly a nongovernmental organization. It describes itself as a joint venture of the Israeli-American Council and IDC Herzliya, Israel’s first private university, which markets itself toward international students and IDF veterans. Additionally, Act.IL is sponsored by the Maccabee Task Force, a group formed by American billionaires Sheldon Adelson and Haim Saban in 2015 to combat the boycott, divestment, and sanctions (BDS) movement. (Adelson is also a prominent donor of IDC Herzliya, where he endowed a school.)

Act.IL itself is the creation of Yarden Ben Yosef, a commander in the IDF reserves who served on active duty in special combat intelligence. Yosef previously organized social media “Situation Rooms” during the 2012 and 2014 Israel-Hamas conflicts, in which college students mobilized to spread pro-Israel hasbara. In a 2017 interview with the Forward, Yosef explainedthat Act.IL’s purpose is to regularize this model of influence operations. Act.IL’s staff, which includes other former IDF intelligence officers, claims to maintain contact with Israeli military and domestic intelligence services.

According to internal documentation, Act.IL received $1.1 million in total funding from 2017‑2018.

The Act.IL app assigns its users “missions” to advance Israel’s public image. These missions typically involve amplifying positive social media posts about Israel or, alternatively, bombarding unfavorable posts with negative comments and mass content moderation reports. By design, such actions are indistinguishable from organic social media activity. In internal documentation, Act.IL refers to this as a “no logo” strategy:

One of the most unique aspects in our activity is our “no-logo” strategy. The no-logo strategy allows anyone to use our content, [sic] and makes it easier than ever to reach audiences that aren’t necessarily pro Israel since they look at the content without a bias that is based on who created the content.

Each task yields a certain number of points. Rather than attempt to integrate with social media APIs (and potentially run afoul of anti-spamming rules), Act.IL relies on an honor system by which users track and report their own completed missions. Accumulating enough points earns a series of Bronze, Silver, and Gold-level badges in categories like “Resolute Redditer,” “Quora Questionner,” and “Intrepid Instagrammer.” The app’s roughly 17,500 registered accounts are ranked on a series of leaderboards.

In addition to a steady supply of new missions, Act.IL provides users with a “library” of pro-Israel research and talking points. Many of these documents complement conventional Israeli public diplomacy goals by, for example, highlighting the success of the Israeli tourist industry or focusing on the terrible toll of Hamas terror attacks.

The archive also contains research dossiers on perceived anti-Israeli threats, some compiled using intrusive open-source intelligence techniques. The predominant focus of these documents is on the BDS movement and its embrace by some younger members of the Jewish diaspora. One such dossier, “Americans Inside Palestine Live (a Facebook Group),” systematically doxxes dozens of U.S. political activists over nearly 300 pages, all of whom are alleged by the author to “walk with Nazis.” Their profiles, friend lists, and posting and “like” history (sometimes five years’ worth) are scrutinized at length. None of this personally identifying information is redacted in the original documents.

In its quest to generate positive attention for Israel, Act.IL has also generated attention for itself, much of which is negative. On Twitter, for instance, an account called “Behind Israel’s Troll Army” broadcasts each of Act.IL’s surreptitious missions to its 3,700 followers. Anti-Zionist and antisemitic commentators claim, frequently, that Act.IL is part of a deep-rooted Israeli conspiracy. In the face of such vitriol, Act.IL remains silent. The app does not even have a Twitter presence — or, at least, not a formal one.

Act.IL During the May 4–5 Hamas Terror Attacks and IDF Air Strikes

The DFRLab monitored Act.IL during May 4–5 and found that it initiated a coordinated influence campaign roughly 36 hours into the conflict. Rather than administer individual missions from the app, however, Act.IL created a special web-based landing page that could be publicly accessed and shared.

This landing page marked an attempt to centralize Act.IL messaging efforts. It provided users with downloadable infographics and talking points, as well as useful web links. It was stated that the page would be continually updated with new information and missions, although it never was.

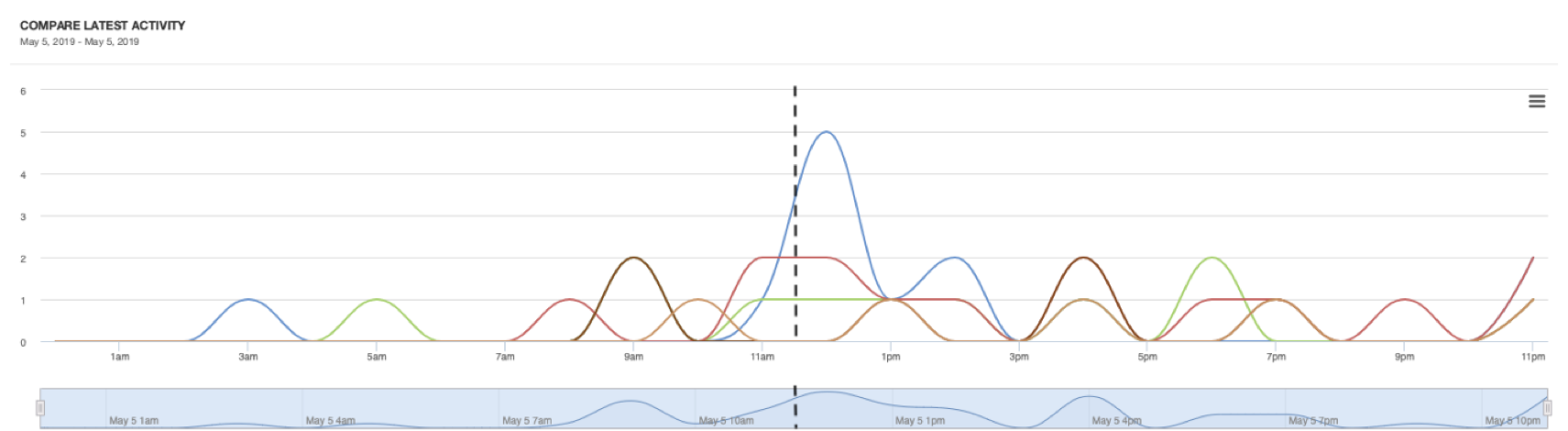

Although the DFRLab conducted a WhoIs search, it was unable to determine when, precisely, the landing page was created. Act.IL publicized the landing page in an email blast to its users, which the DFRLab received at 12:05 p.m. EDT on May 5. Twitter promotion of the page began shortly before this time, as did a special Act.IL app mission that directed users to it.

Despite attempts to activate the Act.IL app’s roughly 17,500 users, the page received scant interest. According to an analysis of direct web traffic using SimilarWeb, the page received roughly 300 visits, 56 percent of which came from the United States, 36 percent from Israel, and the remaining 8 percent from Russia.

Meanwhile, according to an analysis of social media referrals using CrowdTangle, the page received just 243 total Facebook interactions (combined likes, shares, and comments.) Its largest Facebook referral came from the page of the Israeli-American Council, although the post was subsequently deleted. Its largest Twitter referral was due, ironically, to a series of tweets by the “Behind Israel’s Troll Army” account.

Website users who chose to “Comment on Articles on Social Media” were directed to a series of missions in the style of the Act.IL app. These tasks were intended to amplify pro-Israel comments or call out alleged bias in media coverage. They targeted Facebook, Twitter, and Reddit and trained their criticism on NBC News, BBC News, Sky News, and the Guardian.

Two missions sought to amplify a Facebook post and tweet by HonestReporting, an English-language nonprofit that is dedicated to “Defending Israel From Media Bias.” Because HonestReporting has a strong independent social media presence (81,000 Facebook likes and 31,000 Twitter followers), it is not possible to distinguish the influence of the Act.IL app from HonestReporting’s organic base of support. It was excluded from subsequent analysis.

Nine other missions, however — four on Facebook and five on Twitter — focused on boosting the messages of social media users with small or nonexistent followings. These offer new insight into Act.IL’s targeting strategy and impact.

On Facebook, Act.IL sought to amplify pro-Israel comments on news articles that tracked the unfolding conflict. These comment sections, with hundreds or thousands of active participants, attracted fierce partisans on both sides. They constituted the heart of the information war being fought on Facebook.

Most of these targeted commenters were closely connected to the Act.IL organization and its partner organizations. According to LinkedIn, three of four were alumni of IDC Herzilya, Act.IL’s university sponsor. One user had worked for Act.IL in the past, and another was an active employee. This suggests that, rather than rely on organic social media activity, Act.IL deliberately seeds narratives with the intent of using the Act.IL app to promote them.

Two of four of these comments were liked by a largely identical list of Facebook pages. These pages are broadly pro-Israel. One, “We Do Remember Khaybar,” is explicitly Islamophobic. It is likely that these pages are under the operation of the same individual or a group that coordinates through the Act.IL app. No such links are disclosed on the pages themselves.

Because of the closed nature of the Facebook API and the fact that targeted comments were on heavily trafficked pages, it is not possible to make an assessment of the quantitative impact of the Act.IL app. Such an assessment can be made on Twitter, however.

On May 5, Act.IL directed users to “LIKE and RETWEET” five tweets by four Twitter accounts. Two of the accounts lack profile pictures or established Twitter histories, both indicators of inauthentic behavior. Additionally, none of these accounts had significant followings nor did any follow each other. The largest account had 125 followers; the smallest just two.

A Sysomos scan plotting the retweet cascades of these five messages identified abnormal patterns of behavior. Shortly after the first publicity of the Act.IL landing page, all five tweets saw an increase in the attention they received. One tweet, which went unnoticed for seven hours, was suddenly retweeted five times in the space of a single hour and fourteen more times thereafter. Among the Twitter accounts responsible for this amplification were two that appear to belong, respectively, to Yarden Ben Josef, Act.IL’s Chief Executive Officer, and Tom Berman, Act.IL’s Chief Operating Officer.

Such organic behavior is improbable. Although estimates of tweet half-life (the amount of time in which a tweet receives 50 percent of its total remaining engagement) vary widely, according to a study by Wiselytics, that figure is 24 minutes. A conservative estimate suggests that there is less than a 1 percent chance that a given tweet will receive a single retweet after its seventh hour of life — much less the entirety of its engagement.

In total, these five tweets received 59 retweets from 28 unique accounts. Only a single one of these accounts, “LOVE Israel,” boasted more than 1,000 followers. The average follower count hovered around 100. Although few of these accounts showed signs of regular use, neither did they show signs of obvious automation.

If an account retweeted one of the five tweets in the dataset, it was likely that it would retweet another, despite lack of obvious connections between them. Two accounts chose to amplify all five tweets and four accounts chose to amplify four. In total, 80 percent of the retweets came from accounts that amplified multiple tweets in the dataset.

Nevertheless, despite evidence of coordinated social media manipulation, the impact of this amplification effort was negligible. Following significant logistical preparation and promotion efforts by Act.IL, the app elicited an average of just 12 retweets for each of the messages it targeted. This represented an activation rate of just 0.07 percent of its registered userbase.

Conclusion

In theory, the Act.IL app represents a future model for influence operations around the world. Sympathetic users are welcomed into an online community, equipped with talking points, and incentivized to participate in centrally planned “missions.” Because of the nature of the coordination, this activity goes unnoticed by other social media users, nor can it be detected by the platforms themselves.

In practice, however, Act.IL appears to struggle with user retention. Even amid the most serious escalation between Israel and Hamas since 2014, an urgent email sent to roughly 17,500 users translated into an inconsequential blip in a much larger digital dialogue.

The evidence of Act.IL’s coordinated social media manipulation efforts risks drawing the authenticity of Israeli public diplomacy efforts into question; but the app’s negligible activation rate among its userbase demonstrates that it generated little tangible impact.