Project Description

Copyright: Foreign Policy, November 13, 2015.

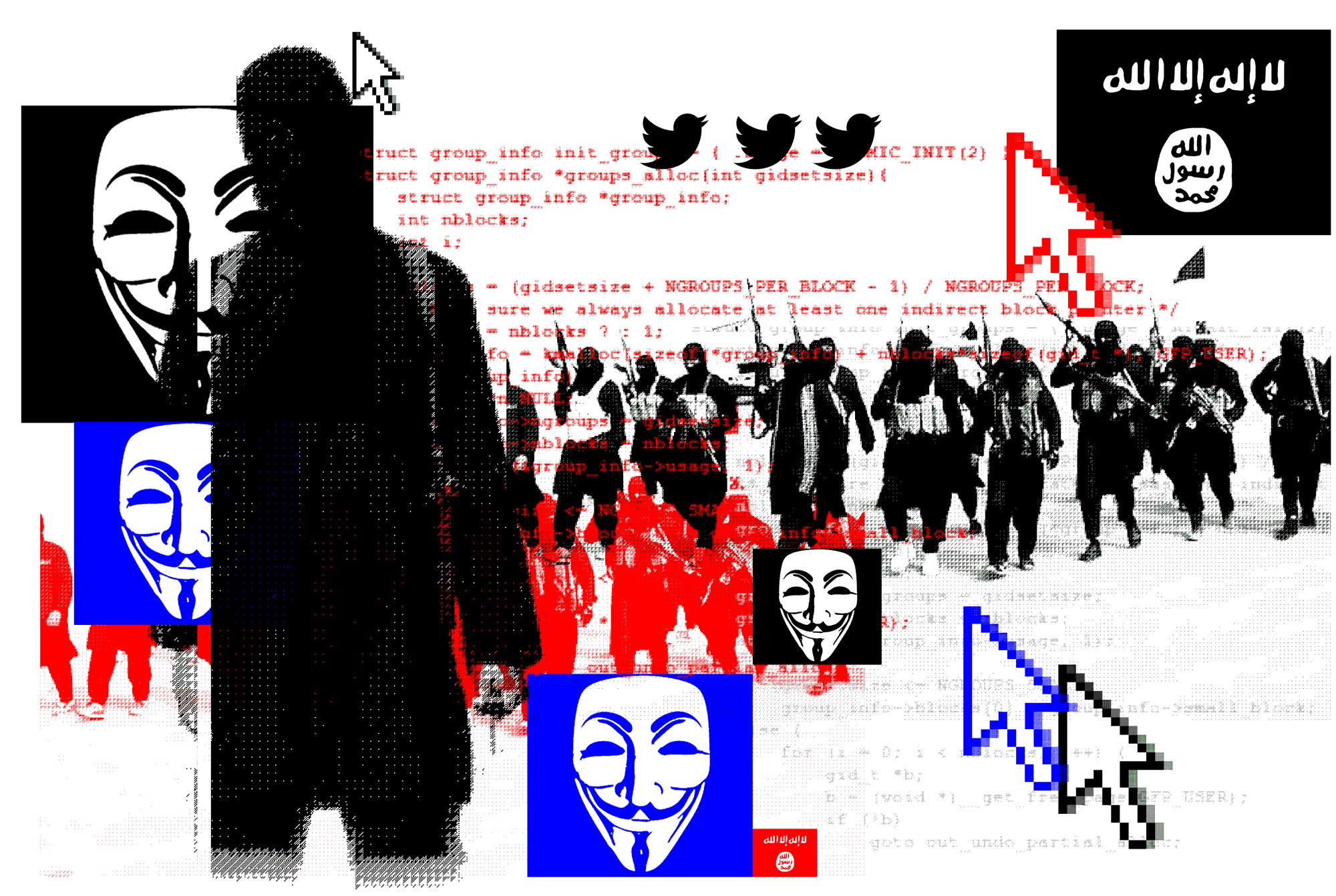

For more than a year, a ragtag collection of casual volunteers, seasoned coders, and professional trolls has waged an online war against the Islamic State and its virtual supporters. Many in this anti-Islamic State army identify with the infamous hacking collective Anonymous. They are based around the world and hail from every walk of life. They have virtually nothing in common except a passion for computers and a feeling that, with its torrent of viral-engineered propaganda and concerted online recruiting, the Islamic State has trespassed in their domain. The hacktivists have vowed to fight back.

The effort has ebbed and flowed, but the past nine months have seen a significant increase in both the frequency and visibility of online attacks against the Islamic State. To date, hacktivists claim to have dismantled some 149 Islamic State-linked websites and flagged roughly 101,000 Twitter accounts and 5,900 propaganda videos. At the same time, this casual association of volunteers has morphed into a new sort of organization, postured to combat the Islamic State in both the Twitter “town square” and the bowels of the deep web.

Chase, who has since shifted his focus to other pursuits, boasts a story typical of those volunteers who work to track and counteract the Islamic State’s online propaganda apparatus. Few of these hacktivists are hood-wearing, network-cracking, Internet savants. Instead, they are part-time hobbyists, possessed of a strong sense of justice and a disdain for fundamentalists of all stripes. Many, but not all, are young people — some are more seasoned, former military or security specialists pursuing a second calling. The oldest is 50. These hacktivists speak of a desire to “do something” in the fight against the Islamic State, even if that “something” may sometimes just amount to running suspicious Twitter accounts through Google Translate.

This is something new. Anonymous arose from the primordial, and often profane, underground web forums to cause mischief, not to take sides in real wars. The group gained notoriety for its random, militantly apolitical, increasingly organized hacking attacks during the mid-2000s. Its first “political” operation was an Internet crusade against the Church of Scientology following its suppression of a really embarrassing Tom Cruise video.

In time, however, Anonymous operations became less about laughs and more about causes, fighting the establishment and guaranteeing a free and open Internet. In 2010, the group launched #OpPayback, retaliating against PayPal for, among other things, suspending payments to WikiLeaks following the publication of a trove of classified U.S. documents. This was followed by a cascade of increasingly political operations: in support of the Occupy Wall Street movement and the Arab Spring protests; against the CIA and Interpol; against Muslim discrimination in Myanmar; and on behalf of democratic activists in Hong Kong. Most recently, Anonymous launched a muddled campaign against purported members of the Ku Klux Klan. As Paul Williams, a hacktivist writer and occasional documentarian, writes in a colorful history of the group, “Anonymous had come to the conclusion that they were no longer abstractly playing with scatology and paedo bears.”

Today, in the fight against the Islamic State, the hacking collective finds itself split by a potentially existential crisis. If Anonymous defends the unrestricted use of the Internet, should this guarantee not apply to everyone, including Islamic State militants? What exactly does it mean when members of a group formed to flout authority find themselves sharing many of the same goals as the U.S. government? In public and private debates that range across cyberspace, self-identifying Anonymous members struggle to reconcile the group’s past with its uncertain present. Although some anti-Islamic State operatives now disavow their connection to Anonymous (intending to avoid precisely this issue), the distinction is hardly so clear to outside observers. #OpISIS and Anonymous share many of the same members, the same motifs, and the same tactics.

To most hacktivists involved in the day-to-day work of #OpISIS, however, it’s really not that complicated. Writing on a Reddit community forum devoted to Anonymous, one member summed up the anti-Islamic State position simply: “Taking away the free speech from a group that is advocating the end of free speech is delicious fun. Telling someone who’d happily chop off your head and mine on national tv to get lost is delicious fun too.” (The subreddit where this appeared has subsequently been hacked.)

Like most hacktivist groups, #OpISIS is ostensibly flat and leaderless, though day-to-day operations are sustained by a few dozen long-serving members who form the concrete core of the movement. In turn, they guide the efforts of hundreds of volunteers. Fragmentary groups tend to focus on different things (taking down websites, tagging Twitter accounts, locating propaganda videos, infiltrating jihadi forums), their roles converging and diverging at random. The result is organic and more than a little chaotic. But it works.

Twitter has long formed the foundation of the Islamic State’s propaganda messaging, granting the group significant strategic reach and complementing many of its battlefield operations. Last year, jihadis advanced on Mosul under the hashtag #AllEyesOnISIS; they manipulated social media chatter to saturate a worldwide audience with the Aug. 19, 2014, video execution of American journalist James Foley and the subsequent public murders of American journalist Steven Sotloff, American humanitarian Peter Kassig, and British humanitarian Alan Henning. A hashtag targeting U.S. citizens, #AMessageFromISISToUS, quickly provoked a flame war between Americans and Islamic State militants.

For months, Twitter struggled to reconcile its intentionally lenient free speech policy with its exploitation as a propaganda tool by terrorists halfway around the world. Twitter had been envisioned as a way to empower voiceless activists in oppressive regimes — not as a weapon of war. Even as Twitter tightened its standards, the Islamic State maintained a robust presence on the service. According to J.M. Berger and Jonathon Morgan’s “The ISIS Twitter Census,” the group’s supporters used anywhere from 46,000 to 70,000 Twitter accounts between September and December 2014.

Furious at the Islamic State’s online presence, some activists jumped on Twitter to take matters into their own hands. One of the earliest was a self-described “dyed-in-the-wool American,” going by the handle @MadSci3nti5t. Armed with Google Translate and an extraordinarily profane list of insults, he took to hijacking popular Islamic State hashtags, reporting Islamic State fighters, and trolling them with a mix of jingoistic jeers and aggressively offensive digitally altered photos.

As he explained via Twitter, writing in an informal style typically found on social media, “isis hates rock and roll…and butts. think of them like your over-religious conservative family member that gets offended if u say ‘ass’ at a family gathering.” On the Richter scale of taunts regularly hurled at pro-Islamic State accounts, “ass” barely registers. Many hundreds — if not thousands — of posts dwell on the sex lives of militants. You quickly feel sorry for goats.

Over time, this random sparring has transformed into a system of list-keeping in which suspected Islamic State accounts are logged by volunteers and fed into a database curated by the robotic sentinels of @CtrlSec. Active Islamic State accounts are targeted at random for mass reporting in which dozens of hacktivists flag the account for review by Twitter in a short period of time. This system ensures that the jihadi accounts jump to the front of the line in Twitter’s massive moderation queue.

Although Islamic State supporters have written their own programs to automatically block Anonymous usernames, they have not been able to stay hidden for long. With every Islamic State account that goes dark, hacktivists celebrate with a triumphant “Tango Down.”

Reached by email, a Twitter spokesperson would not comment on the website’s terms of service or reply to questions about whether the system is now being used by anti-Islamic State hacktivists. The spokesperson confirmed, however, that an account must be reported in order to be reviewed and potentially removed from the system. This means that online activists play an important role in bringing Islamic State supporters to Twitter’s attention and review.

This effort, combined with a notable increase in account suspensions and deletions (on April 2, Twitter suspended 10,000 Islamic State-linked accounts in one day), is straining the patience of Islamic State militants who once enjoyed an unfettered social media presence. Increasingly, hacktivists suspect that some Islamic State social media operations are being managed by contractors and volunteers far from the front lines — and perhaps far from Syria and Iraq altogether. Recreating the same Twitter account more than 100 times over is less practical for fighters engaged in a war against at least 11 armed actors and coalitions.

Discussing this shift via Twitter, @MadSci3nti5t sounds almost wistful. “Last summer you could log on and talk to [mujahideen].… i was interested in the syria conflict [and had] been following it for years on twitter. theyre all gone now. now its just media people.”

Yet Twitter remains just one front in the broader fight to kick the Islamic State off the Internet. Hacktivists have also launched a concerted effort to degrade and destroy the group’s news sites, webpages, and bitcoin donation hubs. This is the realm of the more traditional hacking: distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks to overload servers, SQL injection attacks (accessing and “injecting” malicious database code) to hijack websites and corrupt them from within. Both, of course, are illegal under U.S. law.

Most of these cyberattacks have been conducted by the Ghost Security Group (popularly known as “GhostSec”), an elite cadre of current and former Anonymous members, many of whom have spent years bouncing between various hacktivist causes. Via encrypted chat, GhostSec representatives explained to me that their group is composed of a tiny inner circle of members who work “16 hours a day … and 7 days a week non stop” and are supported by a wide net of part-time helpers. These volunteers scour both the surface-level and hidden (“deep web”) Internet to identify and report suspected Islamic State sites. GhostSec now receives nearly 500 tips per day, its members say.

These hacktivists also apply a rigorous review process before a website is cleared for termination. According to GhostSec representatives, each potential target is reviewed by five members — often including a native Arabic speaker — and ranked by level of threat. Hacktivists reserve most of their venom for Islamic State recruitment sites.

“If we break their communication chains it results in less enemy forces to combat,” said @DigitaShadow, one of GhostSec’s longest-serving members (the group has no formal leadership structure). “We feel if we use [this] method that it will save lives in the battlefield through reduction of OPFOR [opposing force] numbers.”

Asked if their destruction of Islamic State websites sets a bad precedent for freedom of speech online, the answer is immediate: “No,” said @DigitaShadow. “Free speech isn’t murder.”

The digital fight against the Islamic State has also expanded into spying and intelligence gathering. Some GhostSec hacktivists make a habit of infiltrating jihadi forums or uncovering the locations and IP addresses of Islamic State cyber-jihadis. This information is then passed on to the U.S. government. In the early days, the hacktivists say, they were sending information essentially to random government email addresses, seemingly drawn from a hat. As time has gone on, however, they have sought to put this intelligence gathering to better use. They have cultivated ties with trusted third parties, those who can bridge the worlds of law-flouting hackers and government agencies.

One such intermediary is Michael Smith, principal and chief operating officer at Kronos Advisory, a small defense consultancy whose location remains undisclosed. He combs through the leads identified by GhostSec, sending many to contacts within the U.S. intelligence community. “I want to help this group manage what basically amounts to a source rating — how accurate their information is and how well it’s received,” said Smith. At this point, he estimates that he forwards about 90 percent of GhostSec’s discoveries to those in a position to act on them.

According to Smith, this open-source intelligence, passed to the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation, proved a critical piece in disrupting a suspected Islamic State-linked cell in Tunisia as militants plotted a July 4 repeat of the Sousse beach massacre (an FBI spokesperson neither confirmed nor denied this account). Thanks to a mixture of Twitter tracking and geolocation via Google Maps, GhostSec beat the militants to the punch. For #OpISIS, news of the arrests was some small validation for a year’s worth of work — and a remarkable about-face for a community that that has enjoyed a typically antagonistic relationship with the U.S. government.

This effort has begun to catch the eye of those in high places. As retired Gen. David Petraeus, a former commander in Iraq and Afghanistan and a former director of the Central Intelligence Agency, commented via email: “[Smith] has shared with me some of the open source data he has provided to various U.S. agency officials, and I can see how that data would be of considerable value to those engaged in counter-terrorism initiatives.”

As its public profile grows, GhostSec has increasingly sought to leave its Anonymous roots behind. Over the course of this piece’s reporting, GhostSec expanded drastically, recruiting and consolidating an array of previously independent anti-Islamic State hacktivists. After a messy schism, the hacking collective became a “Group” with a capital “G,” abandoning its Guy Fawkes masks in favor of swooping gridlines and a corporate-branded website. In the beginning of November, it released a video trumpeting its successes and media coverage in the Atlantic, the New York Times, and more than 20 other outlets. What began as a slipshod effort to chase the Islamic State off the Internet may end as a professional boutique consultancy — very likely the first of its kind.

Of course, the grimly determined hacktivists of #OpISIS are not the only ones intent on drowning out violent jihadis online. Just like the Internet itself, the digital campaign against the Islamic State bursts with its share of the enthralling, perplexing, and weird. Among the most surreal of all these efforts stands ISIS-chan, a campaign begun in the wake of the Islamic State’s abduction and execution of Japanese citizens Haruna Yukawa and Kenji Goto. Some Japanese, beset by a sense of helplessness, began posting cute, black-clad anime characters to hijack Islamic State hashtags and co-opt its digital presence. The multiplying images carry a simple message:

“The ISIS-chan is a personifying character to disturb the propaganda of ISIS through google bombing,” the translation reads. “It’s not what ISIS currently is, but it is what ISIS should be.”

It is a noble attempt to repurpose the Google-bombing tactics once used to great effect against former Sen. Rick Santorum. Unfortunately, such gambits are also at odds with the basic nature of Islamic State propaganda — a steady thrum of headlines so barbaric that they continue to captivate, even if the world is best served by turning away. In the weird world of Internet war, as in real life, some weapons are stronger than others.

It is even the question, according to Smith, that members of the Islamic State’s Cyber Caliphate have asked themselves as some jihadis attack American websites seemingly chosen by pumping random phrases into Google. “Find The Cheapest Car Insurance” and “The Pregnancy Manual,” both websites previously hacked by Islamic State operatives, do not — presumably — have much connection to U.S. national security.

The truth is that, cast against seismic events like the fall of Palmyra or fight for Ramadi, this Internet war looks small. Banning Twitter accounts, eliminating websites, and even identifying the occasional militant will not stop the Islamic State. It won’t necessarily do much to stanch the flow of jihadis coming from around the world to make a new life in — or fight for — the self-declared caliphate. It will never liberate Syria and Iraq.

But it doesn’t have to. The point of the digital campaign against the Islamic State, stated again and again by those hacktivists who now run it, is simply to push back — to mount a resistance where before there was a void. According to @MadSci3nti5t, the gleeful Twitter troll, “how much do i think the internet war matters? i think its important because they need to know people aren’t gonna put up with that crap!”

For those who fight it, however, there is also another purpose. Following a recent interview with Mikro of @CtrlSec, Simon Cottee, a senior lecturer in criminology at the University of Kent, observed how closely Mikro’s background aligned with the sorts of foreign-born Islamic militants he was intent on defeating. Both had grown up in the margins of society; both had seen many doors to opportunity closed too early. But whereas one has found empowerment by declaring holy war on the West, the other has found it through clever use of the Internet, applying his skills in the pursuit of a perceived social good.

Many hacktivists share this desire. With the Islamic State’s insipid spread into cyberspace, they have finally been given a means to achieve it.