Excerpted from The Assassins’ Gate: America in Iraq, by George Packer

On the evening of November 8, 2003, at around 7:40 p.m., a two-Humvee convoy pulled out through the front gate of the American base at the Rashid military camp in south Baghdad. The mission was to pick up a sergeant attending a meeting at the combat support hospital inside the Green Zone. In the rear left seat of the lead vehicle sat a twenty-two-year-old private named Kurt Frosheiser.

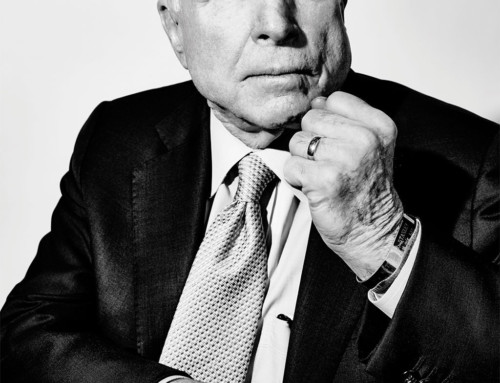

There was nothing obvious to set Private Frosheiser apart from the tens of thousands of other young enlisted men who served in Iraq. He was from Des Moines, Iowa. He had a twin brother, a married older sister, and divorced parents. He had been an indifferent student and a bit of a rebel through high school, and by age twenty-one he was a community college dropout, living with his sister’s family, delivering, pizza, and partying heavily. He had a brash, boyish smile, with his father’s full mouth and lidded eyes; he liked Lynyrd Skynrd and the Chicago Cubs; and one day in January 2003, he flew through the door with the news that he had just enlisted in the Army.

His father, Chris, wasn’t thrilled to hear it. There was a war on terror going on, and the strong possibility of a land war in Iraq. But he didn’t try to argue with his son. In February, Kurt dropped by his father’s apartment around two in the morning after a night out drinking and said, “I want to be part of something bigger than myself.”

Kurt watched the invasion of Iraq on TV looking more serious than his sister Erin had ever seen him. He still had the option to get out of his obligation, but he left home on April 16 for Fort Knox, Kentucky, and basic training. In June the family drove down to see him at Family Day, and Chris Frosheiser was stunned by the transformation: his son, standing at perfect attention on Pershing Field for forty-five minutes in his dress uniform. It was the same in August, when they went back down for graduation: Private Frosheiser, marching, singing with his classmates, “Pick up your wounded, pick up your dead.” The words sent a chill through Frosheiser, but the music, the sharpness and tightness of the formation, the bearing of his son, filled him with pride. Something new and important was happening in Kurt’s life. After the ceremony, Kurt told his father, “You weren’t hard-core enough for me.” Chris always lingered in the gray areas, asking questions; Kurt wanted the clear light of an oath and an order.

They all drove back to Des Moines for their last two weeks together at the end of summer before Kurt would join the First Armored Division in Germany. He partied every night, but the departure hung over everyone, and on the last night, when Erin dropped him off at one final party and turned to look at him, he said, “I know,” and ran off.

“Well, old man, I’m probably not going to see you for two years,” Kurt told his father late that night. They both started to cry, and Frosheiser ran his hand through his son’s crew-cut hair. “I know I’m going to be in some deep shit. But you know me, I’m a survivor.” Frosheiser knew that the words were only meant to comfort him. His son said, “Live your life, old man.”

In Germany, Kurt was bored out of his mind and eager to join the rest of his division in Iraq. On the phone with his father once, he mentioned that it looked like there were no weapons of mass destruction to be found in Iraq. “We’re fucked, aren’t we?” Not necessarily, his father said, there might be other reasons for the war, such as democracy in the Middle East, WMD might just have been the easiest to sell to the public. Kurt’s officers at Baumholder prepared him and the others for what had become guerrilla warfare in Iraq, telling them not to pick up trash bags, not to take packages that kids would rush up to give them, and when Kurt repeated it all to Erin she couldn’t begin to imagine herself in such a place, where a mother like her couldn’t let her children outside the house for fear that something would explode.

Then suddenly Kurt was on a transport plane to Kuwait. By the end of October he was in Baghdad, just as the Ramadan Offensive was heating up.

On November 6 he managed to get online and e-mailed his sister: “Our sector that we patrol is a good one we don’t get shot at that much nor do we find IED’s (improvised explosive device) that’s their main way of attacking us they usually put them in bags but now their putting them in dead animals or in concrete blocks to hide them better. It’s kinda scary knowing their out there but like I said our secter is pretty secure so I’ll be allright.” Writing to his father about his first mission out in the city, an uneventful night drive, Kurt was more explicit: “I found myself thinking that I’m in a country where a lot of soldiers lost their lives but where we at it was so quiet except all friggin dogs barking the Iraqs hate dogs so they’re all wild probably never had a bath their whole lives this country is a shit hole they dont have plumbing so they dig little canels and let all the shit and piss run into the streets it smells so fucking in some places and from what th eother scouts who have been here from the beginning theyre places that smell so bad you almost throw up. From what I see its goin to take a lot longer than Rumsfeld and G.W. are saying to get this shit hole up and running.” He spoke to his father once briefly on the phone. “IEDs, old man, IEDs,” he said.

On the evening of the 8th, Kurt was sitting on his bunk, sorting and counting his ammunition, when word came of a mission to the combat support hospital. He was training for his license as a Humvee driver, and he jumped at the chance to experience driving through Baghdad by night. In his few days with the battalion he had already earned a reputation as a hard worker who was quick to volunteer. He and his best friend in the unit, Private Matt Plumley of Tennessee, raced each other to the vehicle. Because the right rear door was hard to open, they both headed for the left. Kurt got there first.

Five minutes out of the base, as the convoy was cruising north toward downtown Bgahdad, on the left shoulder of the dark highway thirty feet ahead two 130-mm. artillery shells packed with Russian C-4 detonated in a tremendous blast – flash of light, black smoke, flying dirt, smell of explosives. The legs of the driver, Private First Class Matt Van Buren, were torn with hot chunks of shrapnel, but he accelerated another few hundred yards along the highway…until the staff sergeant sitting next to him, Darrell Clay, told him to stop.

A muezzin somewhere began calling the faithful to prayer. In the back of Humvee, Kurt was slumped in his seat. When Plumley checked his pulse, there was none. He had been looking out the window – which had no protective glass – his head turned to the left and a piece of silvery metal 1 3/4″ by 1/2″ by 1/2″ traveling upward had penetrated the right side of his skull just below the Kevlar helmet between the eye and ear and breached his brain. Private Kurt Frosheiser was airlifted by helicopter to the combat support hospital in the Green Zone, where he was pronounced dead at 8:17 p.m.

At six-thirty CST the next morning, a Sunday, the phone rang in Chris Frosheiser’s cramped bachelor apartment in Des Moines. It was a lieutenant colonel in the Iowa National Guard, tow blocks away and trying to find the address. “I have a message from the Army,” he said tersely. Frosheiser knew then, because the week before he had asked an officer what to expect if something happened to Kurt, and the officer had said a phone call if wounded, a visit if killed. Frosheiser met the lieutenant colonel outside the building and invited him in, going through the motions in case it was all a mistake, and they briefly made small talk in the living room. Frosheiser went to the kitchen for a cup of coffee. When he returned, the lieutenant colonel suddenly stood at attention. “I regret to inform you that your son Kurt was killed as a result of action in Baghdad.”

“Not Kurt! Not Kurt!”

Chris Frosheiser ran down the hall, and then he ran back into the living room. The lieutenant colonel asked if he could call someone, but Frosheiser was already calling Erin, and then a friend who drove him to the house of his other son, Kurt’s twin, Joel. Frosheiser banged on the window, shouting, “It’s Kurt, it’s our Kurt!” and then he and Joel drove together to the suburb where Erin lived. The rest of the day and the following days were a blur of tears and friends and wine and exhaustion.

On November 11, Veterans Day, Kurt’s battalion, the 2-6 Infantry, gathered in formation at the American base in south Baghdad for a memorial service. John Prior was there, and so was another captain, Robert Swope, who later wrote an account of the ceremony:

In the background are voices of people talking, vehicles passing, and helicopters overhead. Some birds intermittently fly over us. A butterfly goes by. I see one of the Iraqi translators who works in the TOC sitting in a chair reading a paper while the rest of the battalion stands in formation. At 1430 the ceremony is supposed to begin, but it doesn’t start until 1448 because we have to wait for a couple generals to arrive.

The memorial ceremony begins with an invocation by the chaplain, and then the battalion commander and the company commander both speak. Two privates who knew the soldier follow them. One of the privates chokes and starts tearing up while giving his tribute. I look around me and out into a sea of sad faces and in the very back of the battalion formation I see that one of the female soldiers attached to our unit is crying.

A bagpiper plays a crappy version of “Amazing Grace” and halfway through it doesn’t even sound much like the song anymore. The soldier who plays “Taps” later on at the end of the ceremony does a much better job.

After “Amazing Grace” but before “Taps” begins, the chaplain reads a few verses from the Bible, and then gives a memorial message and the prayer. It’s followed by a moment of silence. Then the acting First Sergeant for the company does roll call, yelling out the names of various soldiers in the unit. They all answer, one after another, that they are present. When he comes to the private who died, everything is quiet.

He calls out the name again, and still there is no answer. He does it a final time, using his full name and rank:

“Private First Class Kurt Russell Frosheiser!”

Silence.

And then the mournful melody of “Taps” begins. Midway through the bugler begins slowly walking away, letting the music softly fade out in the distance. Jess walks over to where seven soldiers stand with seven rifles. He gives the order and they fire off three series of blanks, giving him a twenty-one-gun salute.

When they’re finished the battalion commander walks up to the memorial, which is an M-16 with a bayonet attached and driven into a wooden stand. Resting on top of the butt stock is a helmet and hanging down are a pair of dog tags with his name, social security number, blood type, and religion on them. Directly in front of the M-16 and in the center of the memorial stand is a pair of tan combat boots. To the left and to the right of his boots are a bronze star and purple heart ensconced in their silk and velvet cases. A pair of sabers representing the scout unit he belonged to are crossed behind the rifle. Others follow the battalion commander who salutes the memorial representing Private Frosheiser, until all of the soldier’s company has saluted, and the rest of those attending the ceremony can begin…

This is the second time I’ve had to go to a ceremony like this so far this year and I don’t feel comfortable doing it. I walk up to the memorial the way I did last April for another soldier in my company, who we did the same ritual for in a field of dirt next to the tarmac at the Baghdad International Airport. I don’t lower my head and pray or whisper anything as so many others do before me. I don’t lean over and touch the tip of his boots like the sergeant major ahead of me just did. I just salute and then turn and walk away.

Chris Frosheieser wanted to escort his son’s body back from Baghdad. He at least wanted to meet it at Dover Air Force Base in Delaware. In the end, it was enough to receive the coffin at the Des Moines airport with thirty family members and friends and see Kurt’s face one more time. At the wake, Frosheiser tried to say that his son’s courage filled him with awe, but he wasn’t able to express himself well. Kurt received a military funeral after a Catholic service and was buried in Glendale Cemetery.

Frosheiser’s ex-wife, Kurt’s mother, Jeanie, told the local paper, “He loved his land and its principles. He loved Iowa. It’s an honor to give my son to preserve our way of life.” She had become an evangelical Christian, and she said that Kurt had volunteered to fight the forces of evil. This was too apocalyptic for Chris Frosheiser, suggesting some kind of religious war, and it wasn’t how Kurt had talked. On the night of the terrible news, Governor Tom Vilsack had called to offer condolences and he had said that he hoped the country’s policies were as good as its people. Frosheiser was troubled by the thought that it might not be so. He kept comparing the president’s oath of office to the oath Kurt had sworn when he became a soldier: Were they carried out with equal seriousness? In January, one of Kurt’s friends from Fort Knox wrote in an e-mail: “I don’t suppose he was in an up-armored HMMV, was he? Probably not, Uncle Sam wouldn’t give us Joe’s the good stuff.” Frosheiser didn’t know the answer, but thinking about it didn’t help a bit with his grief.

The speed of it all, the historical vastness – his boy, in the Army, in Iraq, the Ramadan Offensive, hit in the head – was overwhelming. Frosheiser dreamed that he was in the Army with Kurt, though it was unclear where they were father and son or friends, but both of them were sitting ont he right side and when the explosion came they fell out of the Humvee together and everything was okay. The thought that he hadn’t been with Kurt that night to protect him wouldn’t leave Frosheiser alone, nor the thought that he hadn’t had time to send Tolkein’s The Return of the King, a book Kurt had requested. On his wrist he wrote Kurt’s watch, still set to Baghdad time, and with an alarm that still went off every day at 6:30 a.m., 9:30 p.m. in Des Moines.

For weeks and months he struggled with the meaning of his son’s death, but he couldn’t reach an answer.

Header by Chrippy

Leave A Comment